How to Solve the Personal Style Epidemic

On personal style as glitch, online fashion discourse, and building a style philosophy.

At the beginning of this year, I delved into Zadie Smith’s "Intimations," a poignant anthology of short stories crafted in 2020 amidst the tumultuous onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. I expected it to be a moving experience, if unsettling to a certain degree, to read these stories filled with uncertainty for the future after experiencing those following years. Loved ones passed on, and the rich got richer. Unforeseen was its revelation concerning personal style. In ‘A Hovering Young Man,’ Smith quotes the words of the venerable Susan Sontag: “A style is a means of insisting on something.” As those words unfurled before my eyes, I felt compelled to retreat. A sharp inhale crossed my lips. Initially, I interpreted "insisting" as synonymous with discipline, a trait I knew I lacked. Did this void of discipline signify a lack of style as well?

I am not disciplined. I did not grow up middle class, where more is around the corner if you can wait. Where I’m from, you get what you get before it’s gone. We stand on corners, casting furtive glances around the bend, hoping to get whatever said and done before the real lousy man sees. Eat up fast before it’s passed. I hate doing the work (sticking to a color palette and being loyal to designers or brands), but I love being stylish. Upon revisitation, I acknowledge my lack of discipline, yet I find within me a resolute insistence. I insist on fashioning a genial statement when effervescence courses through my veins. I insist on draping myself in armor, a shield against the mundanity that, at times, suffocates. I insist on weaving echoes of the captivating cool girls from my youth into the fabric of every ensemble.

My journey through fashion's digital domain commenced in the mid-aughts, primarily traversing Tumblr (yes, I have brain rot) and Lookbook.nu. As I muddled through the later years of high school during the rise of “the Gram,” I followed my fair share of Fashion Nova- Dolls Kill- Boohoo fashion influencers. In my senior year, I switched to watching fashion school Youtubers to prepare for my own college debut. For insight on designers, I lurked within the recesses of #hft (high fashion Twitter), and presently, the algorithmic machinations of TikTok serenade me with an array of fashion and style content. My longest-followed fashion creators are Raven Elyse, Rian Phin, and DietBlond.

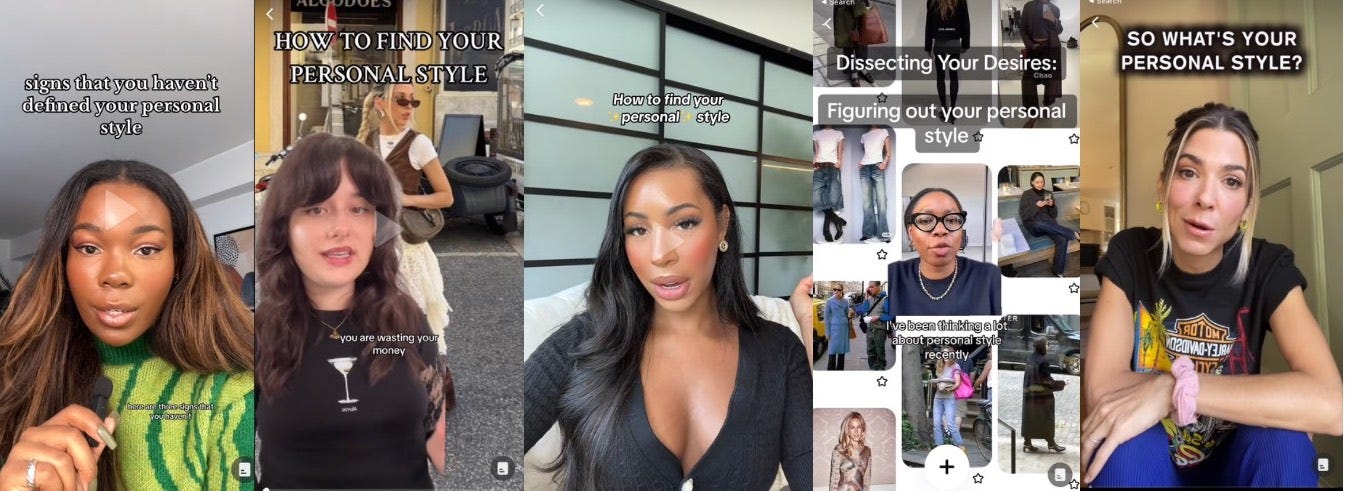

Since late 2022, TikTok has been a conduit for "personal style" content, ushered forth by fashion luminaries who have seemingly deciphered the enigmatic code of sartorial individuality, as well as by humble souls graciously inviting us into their odysseys. The landscape of online fashion discourse has gradually evolved beyond mere recitations of "Styling 2024 trends" and ostentatious hauls. Now, creators are assuming the mantle of educators, guiding us toward discovering our unique modes of self-expression, warning that without such revelation, every ensemble risks languishing in the realm of the mundane.

Personal style becomes a tapestry woven from the threads of our interests, creativity, and innate personality—a veritable masterpiece in cloth. Each thread is meticulously chosen to contribute to a symphony of individuality. It is a departure from the banality of conformity, as those with personal style eschew the capricious dictates of trends to chart their course, governed by an idiosyncratic set of principles.

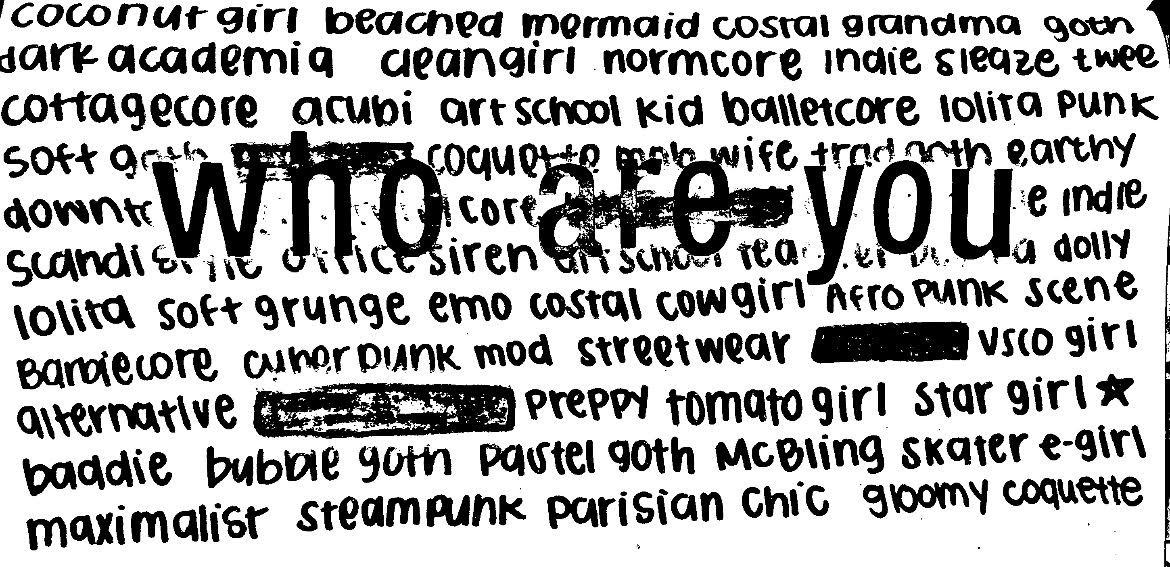

To explain this burgeoning wave of personal style discourse, education-focused creators within the niche lament what they describe as a personal style epidemic. They criticize a fashion landscape cluttered with individuals ensnared in the trappings of "-cores" and aesthetics that bear no semblance to their true selves. Within this wave are also creators willing to embrace vulnerability, bravely confessing their lack of self-knowledge and embarking on self-discovery with us, their virtual audience, as witnesses. Though not identical to the minimalist capsule wardrobe fervor that dominated YouTube from 2014 to 2017, it evokes a similar ethos—a clarion call imploring us to align ourselves with the prevailing zeitgeist and understand what the cool kids are doing.

Despite my generalized skepticism—an ingrained trait I wear like a badge of honor—I still find myself drawn to these conversations surrounding personal style. Yet, as a certified hater, I can't help but tread cautiously, for “hope,” as Lana Del Rey so aptly croons, “is a perilous companion for a woman like me.”

Nevertheless, there's an undeniable allure to these impassioned calls for personal style. They urge us to dissect our desires and forge connections with our unique aesthetic inclinations. Many of these manifestos implore us, as aficionados of fashion, to halt the frenetic pace of consumption. Instead, they advocate for a deliberate examination of what truly captivates our interests, what garments envelop us in an aura of confidence and what accouterments seamlessly weave into the tapestry of our daily lives. This discussion is a significant departure from what the mainstream fashion industry and media demand of us: buy, buy, buy whatever is trending this week and quickly without a second thought.

Embarking on the journey into personal style is embarking on a pilgrimage through the recesses of the self. It compels us to confront profound questions: What brings us joy? What repels us? Who would we like to repel or attract with our dress? How does each garment resonate with the echoes of our past or foreshadow the contours of our future? It is a voyage of self-discovery—one fraught with uncertainty yet brimming with the promise of worthwhile revelation.

I developed my style out of necessity. Money stretched further at the thrift store than at Forever 21, and dupes weren't okay yet. Without access to the newest trends, I realized detaching was less painful than attempting to approximate mainstream coolness. Growing up around non-Black people, I assumed rejection. Fully assimilating, I learned after much pain, would never be possible. Even at my best, exclusion happened. I couldn’t get into the pool, wear the feather extensions, or afford Abercrombie. And even when/if I could, I was still Black. They never let me forget that. I couldn’t afford the Aeropostale polos from the mall, but I could find something no one else would have secondhand. This taught me a lot. I learned what I liked about a garment, how to tell which labels were vintage or worth more than the thrift was charging, and which sweaters would be itchy before ever trying them on. Alone in the USC Goodwill with $20 to my name, I built the core pillars of my style.

Smith’s essay beautifully encapsulated another element I love about this movement for personal style: utilizing fashion and dress to take control of perceptions or even buck against them, not in a way that attempts to sanitize or counteract (respectability) but in a way that genuinely expresses the self. Dress becomes a tangible way to subvert, play with, or create your standard. Outfitting yourself to armor your energy, soften others, and relate to peers.

As young people living through a pandemic and another recession, Donald Trump and Biden, widely televised genocide and shrinking reproductive rights along with everything else under the intertwined oppressions of capitalism, imperialism, and heteropatriarchy, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed with shoulds that are less attainable than ever. With no meaningful control of our outcomes and shaky prospects, what we adorn our bodies with and how we present ourselves can be among the last avenues to take back some semblance of power and independence. As Smith puts it, “Their style is all they have. They are insisting on their existence in a vacuum.” Insisting on style takes you places and connects you. It has taken me to streets I would never have traversed otherwise and connected me to people much like me and much unfamiliar. There is power that emanates from both my sparkly bodycon and oversized cargo fit.

Moreover, in its purest iterations, I see this movement of personal style as a rebellion against the endless boxing and labeling that has coalesced on social media platforms, further expanding surveillance capitalism. From extremely specific fashion “aesthetics” on Tiktok, the MOGAI community of Tumblr, to “all identities in bio” Twitter, we’ve bought into labeling ourselves for the hope of building pseudo-communities in cyberspace. However, the more efficiently we are identified and classified, the easier we can be surveilled, tracked, and sold to. Within this backdrop, personal style is a glitch, as defined by Legacy Russell in Glitch Feminism. Glitch Feminism (one of the most influential reads to my outlook in recent years) explores how marginalized communities create and curate identity through the internet and online spheres, the surveillance capitalism that infiltrated Web 2.0, and how the marginalized utilize social media. Within the short but powerful manifesto, Russell defines glitch as a refusal to participate in the restrictive binaries and categorizations required by surveillance capitalism. Refusal, Russell encourages, is a liberatory opportunity to break apart, dismantle, and create anew. If one’s style is genuinely deeply personal and woven by the textures of their unique experiences, then it cannot be gated into a core. Despite how hard the cynical marketing teams attempt to use nostalgia bait, they cannot box our memories, experiences, and meanings of existence and sell them back to us.

While I find myself intrigued by this movement for personal style, the more I dig under the surface, the more cynical I become. My dubiousness is inherited from Walter Benjamin, the Jewish Marxist theorist whose insights into the fashion cycle have stayed close to me. In the 1930s, Benjamin fled to Paris, where he befriended other exiled intellectuals such as Hannah Arendt, Gershon Scholem, and Theodor Adorno. Once in Paris, he wrote his most influential essays and articles, including the ambitious and unfinished "Das Passagen-Werk" (The Arcades Project, 1938), which, among other topics, explores fashion's social, cultural, and psychological meanings within the context of nineteenth-century capitalism.

Observing Paris, Benjamin saw fashion as a cycle of continuous change propelled by increasing production speeds and trend turnover. He was fascinated by how the shifting aesthetics of fashion mirrored the changing social and political landscapes of its wearers, and the ways in which the fashion industry embodied the “aesthetic of change.” In essence, Benjamin was interested in the aesthetic expressions of change through fashion items and how fashion’s changing aesthetics can stand in for real, tangible social change. Benjamin critiqued this “aesthetic of change” as it worked to induce a “false consciousness” of the proletariat. In other words, fashion trends cycle in and out under the guise of newness, invoking a feeling of progress in society when, in fact, not much has shifted both in the styles and societal landscape. Fashion trends are recreations of the same silhouettes; everything old is new again, and the status quo persists.

Part of me views this personal style movement as another avenue of individualism and consumerism inherent to neoliberalism. On Tiktok, sharing your personal style journey is akin to decluttering your wardrobe of “low-quality” fast fashion, trendy pieces, and garments not worn regularly and, in turn, investing in pieces you “actually love” (which tbh are usually pieces currently on trend). It’s easy to see this as an excuse for continued consumerism, just in this iteration, draped in intellectualism. My feelings are justified when fast fashion conglomerate URBN sponsors creators to gush about how their clothing rental service, Nuuly, helps them identify their unique personal style. I don’t believe receiving clothing monthly that you cannot select is in line with conscious consumption; it’s a fast fashion company weaseling its way into current discourse to expand profits. Further to this point, Devon, a TikTok fashion creator, has shed light on how clothing rental services are an extension of fast fashion. Now that URBN is in on it, it is evident that “personal style discourse” represents the aesthetic of change Benjamin theorized.

Less predatory but still proof of the neoliberal tentacles weaved into this discourse are the personal style coaches, profiting off of sowing wardrobe insecurity amongst the consumers of their content and selling the cure, usually in the form of an eBook or course. Many of these grifters promise a better quality of life, an enhanced connection with the self, an exit plan from fast fashion, and by extension, the end of chasing trends. However, they hardly critique the broader reasons encompassing this mess we find ourselves in nor do they acknowledge how the promise to find any item of clothing you want to represent your inner self ideally is among the most privileged in this fashion industry. Now, these folks aren’t all bad and I understand. I have offered some of these same services and my clients have expressed their gratitude. I and other self-appointed style experts are just filling gaps in the market that neoliberalism always creates. Every facet of the human experience under God’s golden sun is fair game to be commodified and sold—even a journey through the self.

Inherent to this current discussion is a centering of individuality and the individual. Neoliberalism promises that liberation is available on the scale of the individual. Under this paradigm, freedom is synonymous with the ability to consume products perfectly tailored for us. Buying into the neoliberal lie, we believe we can shop our way to self-discovery and toward an equitable fashion industry. While turning away from ultra-specific cores and style aesthetics in pursuit of something more personal could be seen as a glitch, as discussed earlier, it is a continuation of hyper-specific labeling that begets an even more individualized prescription for consumption. We have fully embodied the categorization to the level of disaggregating and pulling apart the self, attempting to get to the heart of some inherent point of view. This is incredibly frightening to me.

While I find it worthwhile to decipher what wearing San-X Crocs to Pilates says about me to the world, I think we’re getting too caught up in this part and not applying enough thought and brain space to what acquiring these objects means for the rest of the world. We’re far too caught up in the individual meaning of our style and forgetting our collective meaning. Considering the collective would require brainstorming and action to dismantle the systems that have left us in this “personal style epidemic.” Having a personal style awakening is standing in for a more critical dissection and participation in destroying the industry as we know it, which is incredibly dull and shortsighted.

I’m torn. While I see a lot of positives, I’m not sold that embracing personal style will liberate any of us from the horrors of fast fashion on an individual or societal level. Again, I’m a student of Walter Benjamin (he was a fashion collector and dealer just like me), so I’m aware of the necessity for dialectical thought and the possibility of revolution. While we can’t shop our way out of a fast fashion-induced collapse, clothing can present a tangible introduction against neoliberalism, patriarchy, imperialism, and all their children. At my environmentally-focused high school, I stopped shopping for fast fashion when I discovered fashion was among the most significant polluting forces on this earth. In community college, suffering through retail jobs, I learned how women make up most of the heavily exploited workforce in fashion. In a Slow Factory Open Education lecture, I learned how discarded textile exports from the West to West African countries continue the legacies of colonialism. While I do not see finding our personal styles as the key to liberation, I am a testament to how fashion, clothing, and histories of dress can present avenues for education and change. Every time a new trend washes over fashion social media, whether it be the minimalist capsule wardrobe, sustainable/slow fashion, or personal style, it seems to lament the same issues in the fashion industry. There are too many low-quality choices out there, so many that they are ruining the planet and our sense of self. I agree with this diagnosis but never with the prescriptions recommended, as they lean far too much into the individual and reject collective action. I’m bored.

The more I think about this, the more I am conflicted about whether possessing a genuinely individual personal style is possible. I wear the styles I have because of my millennial gen-x cusp sister, my friend’s older siblings, the skaters I watched at North Hollywood skate park while I waited for the weedman, abeulitas at the thrift store, artsy white ladies at the farmers markets, and because I grew up online, Twee Tumblr. I’m inspirited by calico kitty coats, my best friend’s beautiful deep and inviting brown eyes, the aloof bitchiness of well-off Brentwood Lululemon moms, 304s, and 2010s Japanese fashion subculture bloggers. My city, loved ones, strangers, traditional/digital media, and experiences have shaped my preferences. My style is an amalgamation, celebration, and recreation of my life’s experiences. I want to suggest we move towards a style philosophy rather than a pursuit of personal style.

A style philosophy is how we think about getting dressed, clothing, the fashion industry, and how we want to relate to it. A philosophy is explicitly built upon the creations of others. It cannot be arrived at; it is an ever-evolving process, a constant dialogue with the world, people, and garments around you.

To Develop a Style Philosophy

Interrogate who you’d like to relate to, confuse, insist on, attract, or repel with your dress.

Consider the life cycle of your garments. How will you obtain them? How will you care for them? Where did they originate from? What impact has it had on the world? How will you get rid of them?

Curate the story you are telling. What is your character in that story? What references are you paying homage to?

Understand why you find some pieces more flattering than others and who taught you to feel that way.

Examine how you interact with the fashion industry and if these actions are compatible with your ethics, morals, priorities, and class interests.

A style philosophy will not solve the “personal style epidemic,” but no one thing will. That’s the problem.

Ahhhh!! Feels like the first fresh thing I’ve read on fashion in a really long time. I love this approach because it solves the problem I’ve been having with personal style which is this question of who AM I? It felt impossible. But what do I believe in? Love? Admire? Want people to see me as? Those answers are immediate. Thank you for this!!

Their purpose is not to to liberate us with technology; rather, it's to control our imaginations and desires. Enticing users to fabricate identities around products people end up not being able to separate what they consume from what they are